I have succumbed to the strange dizziness of a flu that requires me to hold my head as straight as possible; any turns to the side or dips of my head bring on bouts of vertigo. As flus go, this one is quick to let go of the trademark nausea, achiness and gut troubles, but it stubbornly keeps me in the grip of slowly resolving dizzy spells. It’s tough for a busy person such as myself to have to sit still for lengths of time (and not be able to read much!), but I will say there is one silver lining in that I’ve had some time to catch up on my video watching.

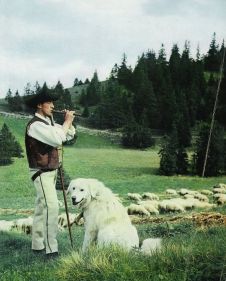

I stumbled on this gem from a young British film maker, Robert Glowacky, who produced this film about the decline of the Slovak Cuvac (pronounced Chuvach), also known as the Slovensky Cuvac, the regional livestock guarding dog of Slovakia.

The tumultuous history of Slovakia is not unique among the countries of central Europe, nor is the history of their white guardian dog. In the University of Aberdeen’s 2002 report entitled “The use of livestock guarding dogs to protect sheep and goats from large carnivores in Slovakia”, author Robin Riggs explains the origins of the Cuvac:

“Livestock guarding dogs probably came to Slovakia from Romania and the Balkans via the Ukraine Carpathians along with other aspects of the transhumance system of intensive livestock grazing in mountainous areas during the gradual Wallachian colonisation from the 13th and 14th to the 18th and 19th centuries. The Tatranský čuvač, Lipták or valaské psi, of which until relatively recently every salaš (temporary sheep dairy farm/fold) had up to 10 for protecting livestock from predators and thieves, became the native breed of LGD. However, by the mid-1920s numbers had declined to such an extent – particularly during World War I – that systematic efforts were initiated to rescue the čuvač as a breed. With International Canine Federation (FCI) recognition in 1965/69 and the establishment of a club for the Slovenský čuvač (as dog breeders re-named the Tatranský čuvač), breeding focused on the production of show dogs, pets and property guardians…. Most salaše still have dogs (čuvač-type or other, usually the Caucasian sheepdog, Central Asian sheepdog, Polish Owczarek Podhalański and crosses thereof) for protecting livestock…”

He goes on to talk about the interesting way in which the shepherds kept their dogs, a way that is seen frequently in the film:

“…but they are almost always chained to stakes or trees around the fold and milking pen, though at some camps they are released at night. Chaining dogs alters their behaviour (I have found many at salaše to be abnormally aggressive or, when approached closer, rather timid, sometimes ecstatically playful or excessively solicitous of attention) and limits their ability to protect livestock to the length of the chain (Coppinger and Coppinger 1994) or barking to alert shepherds. Many of Slovakia’s chained dogs also suffer excessively as they are deprived of social interaction and some are left on open pastures without access to shade and water.”

Riggs goes on to explain that this was not, historically, how these dogs were kept, but that the war and changes to the number of predators in the area led to shepherds chaining the remaining Cuvac instead of allowing them freedom to patrol.

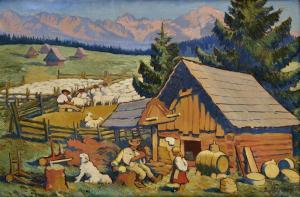

Jan Hala, 1927

“In his illustrations accompanying the tale [Old Bodrik and the Wolf], Martin Benka (1888-1971) drew a čuvač, unchained and therefore able “to circle the sheepfold” and go out from the farm to challenge a wolf, bear and fox (Vulpes vulpes), as in the story. Jan Hála’s illustrations from the 1940s (e.g. in Hála 2001: 68, 78) and his description (p.94-97) of the čuvač guarding flocks by day and salaš by night also eloquently portray the continued traditional use of LGDs in Liptov. In 1953, however, Kováč (p.263) wrote that guarding (but not herding) dogs could be chained and some early 1960s photographs (e.g. in Podolák 1982) show LGDs chained up in the Nízke Tatry. At this time, hunting had decimated the wolf population (reviewed in Voskár 1993 and Hell et al 2001) and bears were half as numerous and more restricted in range than presently (reviewed in Janík 1997, Hell and Slamečka 1999), so it may be that there was no longer a pressing need to protect flocks effectively. Perhaps the total number of dogs was reduced to cut costs, or smaller ones favoured for the same reason (T. Krafčiková pers. comm. 2003). Remaining dogs may have been chained for convenience. Podolák (1967: 109) reported that tame LGDs were taken out to pasture but “dangerous” ones were chained near the koliba (shepherds’ hut) during the day and released at night.”

The subsequent paragraphs offer alternate explanations for the widespread use of chaining Cuvac, both gleaned from reviewing recorded 20th century history and in more recent conversation with Slovak shepherds. While I was reading it (and I greatly encourage you to as well!- page 18 and beyond), I was struck by the similarities to some of the advice encouraging people here in North America to chain their LGDs. Some of the pressures the Slovak people came under in the last century are also reminiscent of the mistrust and population increase that our dogs are currently subject to. Further, mention of the fear that the Slovak people feel when contemplating the Cuvac was evident even in the first half of the 20th century.

“Interestingly, illustrator and writer Jan Hála, who lived among rural people in the region below the Tatras from 1923 till his death in 1959, noted that “Boli to psi ani medvedina, celá dedina saich bála”, “The dogs were like bears, the whole village was afraid of them” (Hála 2001: 97).”

This fear informed some of the local laws and customs: for example, the one that allows any sheepdog more than 200 meters from a flock to be shot on sight.

Could it be that the attempt to create a more aggressive dog (by chaining) to defend against predators and strange people resulted in a dog whom no one could trust and therefore needed to be continuously chained? Riggs certainly points to this as a reasonable, albeit ironic, possibility. It would seem, too, that the handling skills of the shepherds and their employees often border on cruel, continuing the erosion of relationship between dog and man.

“I have seen several shepherds beat sheep with sticks and kick them unmercifully and suspect the same sometimes happens to their dogs; a shepherd in Horehronie needed 17 stitches after he rather unwisely hit a Caucasian sheepdog when drunk (S. Finďo pers. comm. 2001, Finďo 2001: 13) while some LGDs placed at farms in Liptov and Turiec are shy of or aggressive towards men carrying sticks. I have frequently been surprised by how little some shepherds know about dogs. Today’s shepherds also seem to be much less concerned about loss of sheep than their predecessors, who often slept by the flock to guard it (I. Zuskinová pers. comm. 2003). It may be, therefore, that a further factor in the decline of the LGD tradition has been the gradual loss of traditional skills and knowledge coupled with an increased desire to solve short term problems (e.g. a wandering dog) in the quickest and easiest way (i.e. by putting it on a chain).”

All is not lost, however, as is seen both in Glowacky’s film and in Rigg’s report. Shepherds and citizens of Slovakia alike still greatly value the Cuvac, their history, and their inborn ability to defend the defenseless. It is clear that careful breeding selection, appropriate training and working to change Slovak attitudes are all vital parts of bringing the Cuvac back to their former position of trusted, unfettered guardian – but it is also clear that they have found dedicated people to champion their cause. If the rewilding of Europe is to be successful, and harmony is to be restored to the ecosystem, the restoration of the Slovak Cuvac and others like them are the only hope for continued peace between the domestic and the wild.

For the full text of the report, follow this link: Livestock Guarding Dogs to Protect Sheep and Goats from Large Carnivores in Slovakia (PDF Download Available). Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237703700_Livestock_Guarding_Dogs_to_Protect_Sheep_and_Goats_from_Large_Carnivores_in_Slovakia

For a brief overview of Slovakia, current and historical, follow this link: Encyclopedia Brittanica, Slovakia

If the video in this post does not load, follow this link its original home on Vimeo: Bringing Back Bodrik